Introduction

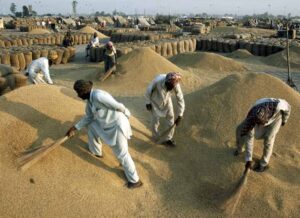

India is an agriculturist nation. The history of agriculture in India dates back to the Indus Valley civilization era and even before that in some parts of southern India. The agriculture sector is one of the most important industries in the Indian economy. Agriculture is the primary source of livelihood for about 58% of India’s population, contributing about 18 per cent to India’s GDP.

Despite such huge numbers nothing important or revolutionary has been done for the farmers of the nation. Majority of the farmers even after working hard day and night, in scorching sun and dreadful winters continue to live a pitiable conditions.

Many times the Farmer’s produce got destroyed due to natural calamity. If their produce managed to reach the Mandi’s they had to face the exploitation of the Arhtiya’s, and having handed over their produce to such Arhtiya’s they could never get the rightful price of their produce.

There is no doubt that the previously prevailing laws have failed to stand true to their objective and have left the innocent farmers to mere mercy of the greedy Arhthya’s. This ultimately led them to loosing hope and giving up their lives.

In this article we shall discuss the old APMC Act and FPTC Act, 2020 , the provision these act held for farmers and how much they actually helped.

Agricultural Produce Marketing (Regulations) Act, or APMC Act

In the post-Independence era, the first reforms in agriculture marketing were initiated in the 1960s and 1970s, when the states enacted Agricultural Produce Marketing (Regulations) Act, or APMC Act. The organised APMC markets came into existence so that the farmers in their vicinity could bring in their produce for sale. APMC markets were to have physical auctions to ensure transparent price discovery.

All states, except Kerala, Jammu and Kashmir and Manipur, enacted such laws.

The APMC Acts mandated that the sale/purchase of agricultural commodities is carried out in a specified market area, and, producer-sellers or traders pay the requisite market fee, user charges, levies and commissions for the commission agents (arhtiyas). These charges were levied irrespective of whether the sale took place inside APMC premises or outside it and the charges varied widely across states and commodities.

In the initial years, APMC Acts helped remove malpractices and freed the farmers from the exploitative power of middlemen and mercantile capital.

The golden period for APMC markets lasted till around 1991. With time, there was a palpable loss in growth in market facilities and by 2006, it had declined to less than one-fourth of the growth in crop output after which there was no further growth.

This increased the woes of Indian farmers as market facilities did not keep pace with the increase in output and regulation did not allow farmers to sell outside APMC markets. The farmers were left with no choice but to seek the help of middlemen.

Due to poor market infrastructure, more produce is sold outside markets than in APMC mandis. The net result was a system of interlocked transactions that robs farmers of their choice to decide to whom and where to sell, subjecting them to exploitation by middlemen.

Over time, APMC markets have been turned from infrastructure services to a source of revenue generation. In several states, commission charges were increased without any improvement in the services. And to avoid any protests from farmers against these high charges, most of these were required to be paid by buyers like the FCI.

In Haryana and Punjab, mandi fees and rural development charges for wheat and non-basmati rice purchased by FCI are four to six times the charges for basmati rice purchased by private players. This not only results in a heavy burden on the Centre but also increases the logistics cost for domestic produce and reduces trade competitiveness.

The reforms in market regulation remained slow even after successive governments at the Centre made repeated attempts to persuade the states to make appropriate changes in their APMC Acts.

Finally, the Centre used the constitutional route to address long-pending issues of market reforms by introducing Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce Act 2020.

Farmers Produce Trade and Commerce Act 2020 or FPTC Act, 2020

The FPTC Act, 2020, allows barrier-free inter-state and intra-state trade and commerce outside the physical premises of markets notified under state APMC legislations.

FPTC Act, 2020 and APMC Act comparison

The Act allows farmers to engage in direct marketing, thereby eliminating intermediaries. It stipulates that “no market fee or cess or levy, by whatever name called, under any state APMC Act or any other state law, shall be levied on any farmer or trader or electronic trading and transaction platform…”

The FPTC Act gives farmers the freedom to sell and buy farm produce at any place in the country — in APMC markets or outside the mandated area — to any trader, like the sale of milk. The Act also allows transactions on electronic platforms to promote e-commerce in agriculture trade.

This is the provision which has led to protests, mainly in states like Punjab, Haryana and parts of Uttar Pradesh where apprehensions have been expressed that the Centre may not continue with Minimum Support Price (MSP) for procurement of rice and wheat from farmers. Agriculture Minister Narendra Singh Tomar has stated that the FPTC Act has no link with MSP operations; the legislation does not even refer to MSP.

Although the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Prices (CACP) recommends MSP for 23 agricultural commodities prior to the commencement of Kharif and Rabi seasons, the Food Corporation of India (FCI), in association with state government agencies, largely procures wheat and rice, mostly from Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh, which ensures grain supplies required under the National Food Security Act (about 60 million tons annually).

According to estimates, only some 6% of the farmers get the benefit of MSP operations while other bodies like Nafed, Cotton Corporation of India, etc., do take up MSP operations on request for oilseeds, pulses, cotton etc.

The real reason behind the protests against the new legislation is the fear that it would lead to huge revenue losses. It is only in Punjab and Haryana, where rice and wheat procurement by FCI is routed through APMC markets. Punjab imposes levies of of 8.5% (market fee 3%, Arhtiya commission 2.5%, rural development cess 3%) on MSP, while Haryana levies around 6.5%. The FCI could go for direct purchase with farmers avoiding the APMC markets, thus depriving commission agents as well as state governments of revenue worth some Rs 2,700 crore annually.

The effect of the FPTC Act on APMC Mandi’s

The effect of the FPTC Act on APMC Mandi’s will depend on the treatment meted out to the Mandi’s and the charges and levies therein.

Out of the 25 states with APMC Acts, no commission is levied under the FPTC Act on notified crops in 12 states. Service charges like Mandi fees on major crops in these states vary from zero per cent to one per cent in nine states and it is two per cent in Madhya Pradesh and Tripura. There is no threat from the FPTC Act to APMC Mandi’s and their business in these states as private traders and sellers will get benefits commensurate with the mandi charges.

The second category of states — Andhra Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra and Telangana — is where service charge for mandi’s is one per cent of the value of produce and commission varies from one to two per cent. Uttrakhand also comes in this category. Karnataka follows these states closely, with total charges at 3.5 per cent. These states can easily bring down mandi charges to 2 per cent or less.

The third set of states includes Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Arunachal Pradesh, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh, where the total charges, including commission, varies from five to 8.5 per cent, the highest being in Punjab followed by Haryana. Punjab and Haryana will not face any challenge from sale outside of Mandi’s as long as paddy and wheat are the dominant crops and are procured by the government. It is in the long-term interest of these states to bring down market charges and commissions to 2 per cent or less to enable APMC Mandi’s to compete with sales outside their premises.

The real threat in some states to APMC mandi’s and their business is from excessive and unjustified charges levied under the APMC Acts. The FPTC Act will only put pressure on APMC markets to become competitive.

A maximum 1.5 per cent of total charges, distributed between market fee and commission, are adequate to maintain and run mandi’s. This will not wean away traders from APMC markets as they will receive the benefits of mandi infrastructure, bulk produce available in one place and save costs required for individual transactions outside the market. The states which are actually interested in farmers’ welfare should keep mandi charges below a reasonable level of 1.5 per cent. This will ensure the co-existence of APMC mandi’s and private channels permitted under the new Act in a true competitive spirit.

Conclusion

The immediate impact of these sweeping changes in India’s agriculture marketing system is expected to result in more private investment in infrastructure such as storage and warehouses and with the competition, the APMCs could also provide better facilities and retain their business.

The states , in farmers’ welfare should keep mandi charges below a reasonable level of 1.5 per cent to ensure the co-existence of APMC mandi’s and private channels permitted under the new Act in a true competitive spirit.

Also there is no doubt that the political propaganda of this nation has once again become a huge hurdle for these laws in its way of benefiting the most important group of citizens.